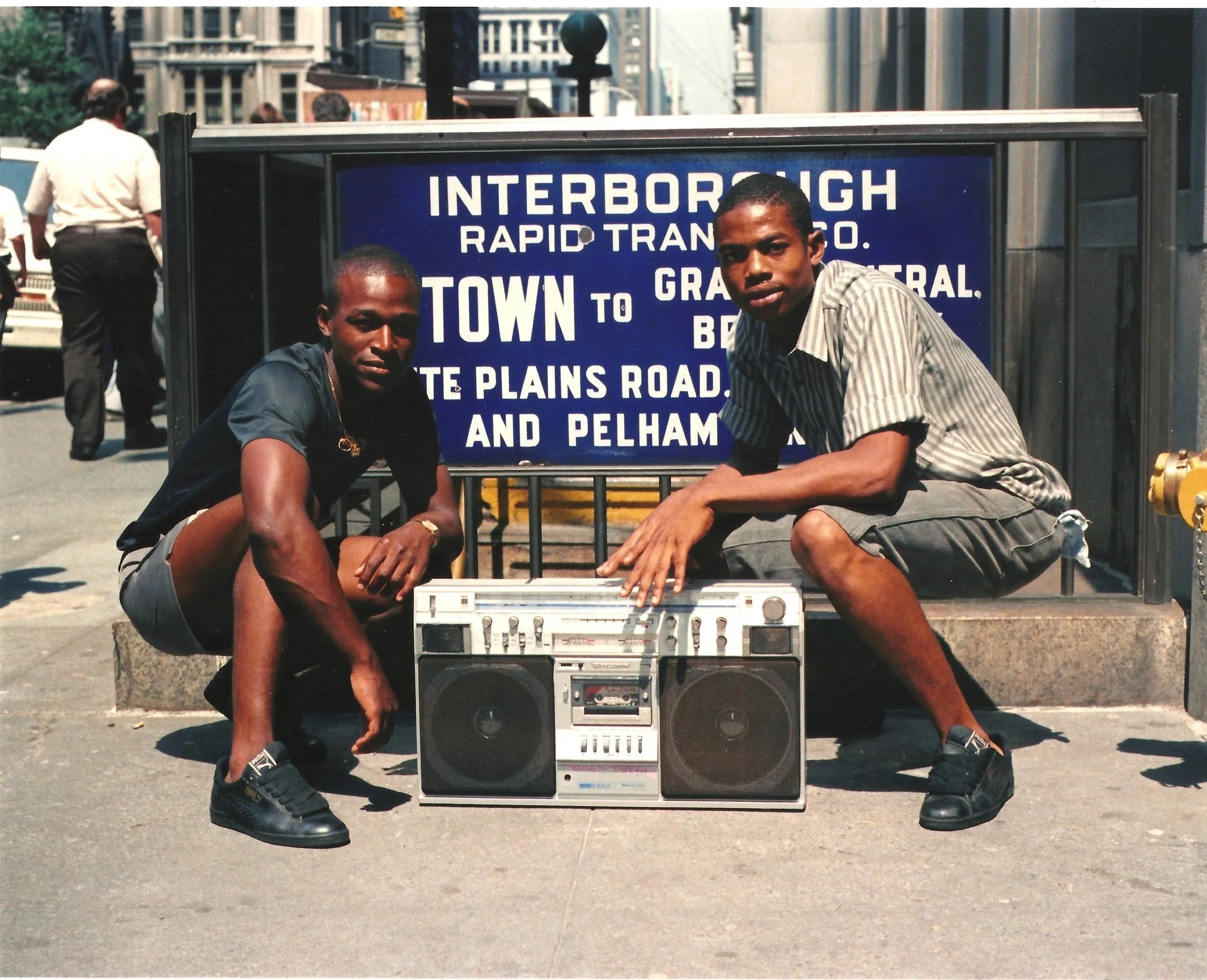

Jamel Shabazz, Untitled. NYC. Circa 1985

Book Review: PIECES OF A MAN By Byron Armstrong, Whitehot Magazine, May 2023

Not so long ago, it was unusual to see the common Black man, woman, or child reflected through the eyes of a photographer, particularly one who truly understood their subject. Not just contextually or in the moment, but rather, the external and internal knowledge of what fashions a person based on race, social class, location, and a period in time — a knowledge that can only come from a shared, lived connection. Photographer Jamel Shabazz was perfectly situated in 1980s New York to be a documentarian for Black and Latinx youth. This was a population that Reaganomics (Reaganism is Black Genocide, Downtown Brooklyn, 1982) and an almost bankrupt city would forget until a crack epidemic, and the ensuing war on drugs projected them through a lens of criminality. Even disgraced former U.S. President Donald Trump infamously led the charge to bring back the death penalty for the Central Park 5, a group of five Black and Latino youth who were accused and convicted, under questionable evidence, for the brutal 1989 rape of a jogger in Central Park. These sorts of images of Black and Brown youth, monsters devoid of humanity, were proliferated in print and broadcast media and made it difficult for the average frightened New Yorker of that time to empathize with them.

Hope and Promise Montreal, Quebec 2014

In the photobook “PIECES OF A MAN”, Shabazz’s photos become a time capsule that illuminates and provides a deeper context for the lives of his subjects between 1980 and 2015. There is no makeup or hint of what you could call formal modeling at play, and Shabazz doesn’t need to rely on a stylist. The people in his camera frame come with their own sense of fashion. In the 1980s and 90s, this is fueled by a heady mix of NYC street culture that includes the fashion sensibilities and attitude of Hip-hop (Inside the Albee Square Mall, Brooklyn, 1984), graffiti and mural art (Writing on the Wall, 1990), a prisoner’s perspective of the industrial prison complex (Central Booking NYC, 1997), motorbike culture (The Sisters 1985), and the impact of the tightening noose of crack cocaine (And Then Came Crack, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1983), police presence (Busted, Flatbush Brooklyn, 1982), and structural decay of a city in the midst of a boom/bust cycle in reverse. There is more that might be lost when viewed from the standpoint of an outsider photographer in search of the sensational, in places with people that help confirm sellable biases. Today, we call it clickbait, but the power of a clicking camera still holds power in the hands of whoever wields it.

Jamel Shabazz, When Two Worlds Meet, NYC, 2013

Where there is hardship, there must be faith to endure it, and Shabazz captures that element through the smiling faces of inner-city youth and their pride in a subculture-inspired fashion moment. Shearling coats, Gazelles, and Lees adorn people who would become the prototype for a marketable look (Partners 1980), even while the reality that birthed the style would be watered down, autotuned, and eventually, co-opted by the corporations that initially resisted it. Shabazz turns the urban environment into a canvas of tagged train cars where the reek of stale urine and sharpies (Triple Darkness 1980) almost emanate from the photo, while at the same time, through the embrace of lovers (Underground Love, NYC) and camaraderie of laughing teen girls (Rush hour 1980) those same trains become the cracks where the proverbial light come in. But also doting fathers (Father and Son, Downtown, Brooklyn, 1985), proud mothers (A Mother’s Love, 1995), mischievous teens (Joy Riding, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1988), and the awe of a child finding their happy place (My Day Will Come Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1980) staring out the window of a bus in Flatbush.

Jamel Shabazz, And then Came Crack, Flatbush Brooklyn 1983

It may be difficult to grasp in this age of Instagram attention, where cheap “influence” can be exercised through the color filter of an amateur’s camera phone, and democracies feel threatened by TikTok marketing schemes lobbed into an algorithm feed like hand grenades.

Before Tyler Mitchell snapped Beyonce for the cover of Vogue magazine, or the art market began to clamor for the Black figure in all its forms, Jamel Shabazz was always right here. In his later 2000s series of work, Shabazz expanded the scope of his view, becoming global in his appreciation of local cultures from the rest of the U.S. to Canada, the Caribbean, Africa, and beyond. He is a journalist-artist with a neutrality that allows the viewer to make up their own minds about what they are seeing and how they should feel and enough depth of emotion in each photo to do so. In the 80s and 90s, Shabazz showed us the lesser-known side of America that would define cool in a pop culture sense for the next three decades. In the early to mid-aughts, he focused on an America divided and united, self-aware and confused, and at war with war (No More Killing, Washington, D.C., 2003), or oftentimes, just at war with itself.

This is ultimately what differentiates Shabazz from a street fashion photographer. Shabazz is more closely aligned with forebears like James Van Der Zee (Church Ladies, NYC, 2005) and Gordon Parks (Merchants of Death, NYC), both Black 20th Century photographers who brought intelligence and insight through images of ordinary citizens that remind us that “Black America” is America, with all its joy, pain, tribulations and promise.

Lorien Suárez-Kanerva Coalescing Geometries Book Cover.

By JONATHAN GOODMAN (BOOK REVIEW PUBLISHED IN WHITEHOT MAGAZINE)

The book Coalescing Geometries is an excellent presentation and analysis of the paintings of Lorien Suárez-Kanerva, who has traveled extensively but who now lives in California. Of a bicultural Venezuelan and American heritage, the artist has expanded her intellectual outlook through extensive study: she has a high honors degree from Berkeley, as well as another degree from the Katholieke Universiteit in Leuven, Belgium. Additionally, she has studied at Universidad de Salamanca and ESADE in Barcelona. Along with painting, her major interest, Suárez-Kanerva is a writer, producing reviews and articles for Art Miami and Whitehot Magazine. Her beautifully designed monograph has been published by Artvoices Art Books, and, in addition to an extensive selection of the painter’s strikingly hued, complex geometric works, a number of essays are spaced periodically along the length of the book. Authors include historian, curator, and editor Peter Frank; the writer and curator Milagros Bello; and the artist herself.

As Frank points out in his lucid introduction, Suárez Kanerva practices a style most accurately described as Neo-Modernism. This means, as the extensive documentation of the artist’s paintings points out, that Suárez Kanerva’s art takes direction from various styles in the century before us, ranging from Cubism to intricate geometries defined as much by color as form. Thus, she looks to a historically driven but very contemporary treatment of a tradition we might well think is oriented mostly toward the past. But this is not so in Suárez Kanerva’s paintings, which are filled with overflowing light, dazzling within the designs the artist has chosen. The brilliant colors of her art cannot be denied, and the complex arrangement of forms, often brought together like the parts of a puzzle, result in a free, highly creative reference to artists from the last century. The truth is that modernism has never really left us, determined as its contemporary practitioners are to find new ways of keeping the tradition alive.

Wheel Within A Wheel 117 2018 Acrylic 40 in. x 40 in.

Not all the essays can be described, but Milagros Bello, an academic, has contributed a fine essay about Suárez Kanerva’s paintings. Bello emphasizes the formal beauty of the art: the swirling, brightly hued geometric patterns that overtake the expanse of the composition. At the same time, Bello uses a phrase such as “cosmic world” to acknowledge the mystical leanings of the artist, whose work suggests a boundless unity without specifying a particular devotional practice–even when she quotes Teilhard de Chardin, the French Jesuit philosopher, as a guide to spiritual matters. Bello is very aware of the artist’s drive toward the depiction of unknown realms, which are outlined indirectly by the nonobjective forms. Bello does a fine job of joining a close description of Suárez Kanerva’s method to the portrayal of her otherworldly concerns.

Wheel Within A Wheel 116 2018 Acrylic 40 in. x 40 in.

The book’s last writings were done by Suárez Kanerva herself. Of a mystical disposition, the artist quotes a good deal from de Chardin, whose buoyant faith, optimistic in the extreme, looks to a time when the preoccupations of people merge with the unseen, but deeply influential force of belief. The stylistic complexity in Suárez Kanerva’s art asserts a resounding affirmation inspired by God, alive in the lucent nature of her efforts.The paintings provide insight by creating an abstraction reminding us both of art history and spiritual development. The essays in the book are excellent; the writers overcome the challenge of interpreting a regularly nonobjective art. While the essayists’ point of view looks closely at Suárez Kanerva’s abstraction, they must also convey the mystical drive in the art. The challenge is to capture the effect of the works, which build abstract patterns of colorful immediacy. The large selection of artworks available in this luminous, informative book reveal the artist’s sensibility, given to light. It is clear that Suárez Kanerva has never stopped searching. WM

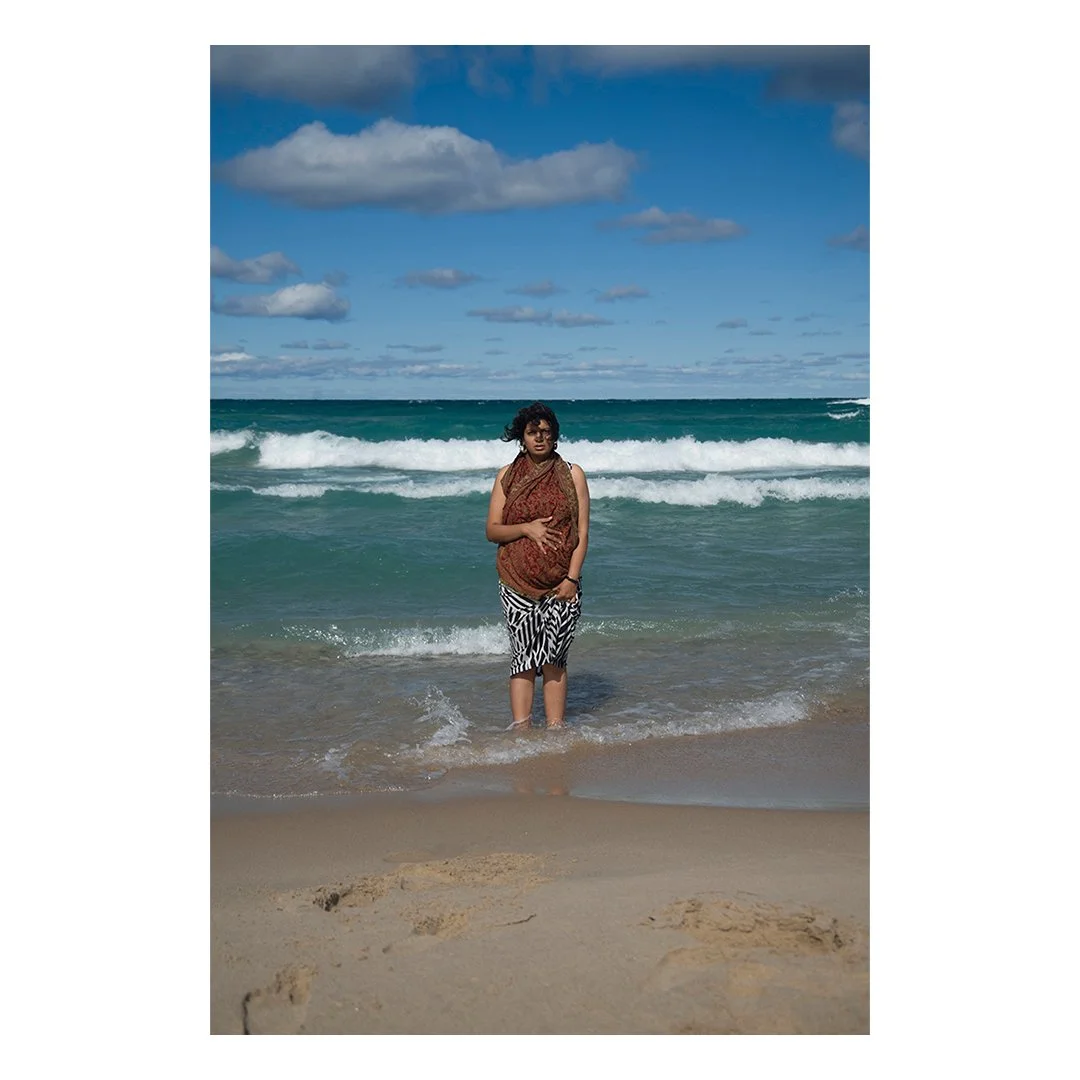

Lali Khalid, Home. In my heart, beating far away. A summer that was, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

By SUSAN VAN SCOY (BOOK REVIEW PUBLISHED IN WHITEHOT MAGAZINE)

Throughout her new book, Home. In my heart, beating far away, artist Lali Khalid weaves her journey of becoming a new mother into her experiences navigating Western culture while seeking to maintain her authentic South Asian heritage and family roots. Imbued with notes of transition, identity and belonging throughout, the work is visually striking in its rendition and profound, if occasionally elusive, in its treatment of these complex themes. The book is prefaced with an introductory essay and foreword written by Professors Allen Frame and Jaspal Kaur Singh and divided into three chapters of 20-23 color photographs each. Khalid, who was born in Pakistan and came to the U.S. to study, immigrated here in 2011, and now teaches photography at Ithaca College.

In the first few pages of Home, we glimpse the artist seated in shadow, backlit by a window, in an impersonal, wooden-paneled bedroom. Clues identify the space as temporary—personal objects on the nightstand and a suitcase open on the bed. Entitled On the last day, her face is shrouded in darkness but her upright posture denotes that she is keenly surveying the situation. She is going on a journey, but we don’t know where. This intuitive sense of “being while traveling” permeates her book. Khalid achieves this in part through her use of the dupatta, a cloth traditionally used as a sign of modesty and for prayer but now worn as more of an accessory in contemporary Pakistani dress. The word dupatta is derived from Sanskrit meaning du-for two, and paṭṭā -for strip of cloth, as it was usually doubled around the head; however, Khalid uses the dupatta to symbolize her homeland of Pakistan and her mother as well as the dual nature of acclimating to a new culture while leaving another one behind. In Khalid’s works, the dupatta appears in many forms throughout the work as a shapeshifter—it can be floating and translucent or dark and looming, indicating the protective yet sometimes burdensome nature of a dual identity.

Khalid, Home. In my heart, beating far away. A number, not a name, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Home. In my heart, beating far away is significant in many ways, including its return of sorts to the photo book. Similar to songs on a CD or album, these photographs can all stand on their own, but when viewed collectively show a narrative progression that yields richer meditations on the intersection of diaspora, acculturation, and motherhood. Like Robert Frank’s use of gesture in The Americans, Khalid uses various forms of cloth—shirts, blankets, dupattas, baby slings, hijabs, sheets, blindfolds, underwear—as transitional objects pulling the viewer from one image to the next. Her works bear some resemblance to works featured in The Museum of Modern Art’s groundbreaking 1991 exhibition Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort, which was one of the first to feature photographers who focused on the home; however, at 30 years old and featuring mostly white photographers, the subject gets a much-needed update from Khalid. Khalid uses the genre of self-portraiture to explore the role of motherhood following along the lines of Diane Arbus, Renee Cox, Catherine Opie, and Annie Wang, among others.

Lali Khalid, Home. In my heart, beating far away. Center within the center, 2012. Courtesy of the artist

Taken over the course of ten years, the photographs are presented chronologically. Chapter one begins with self-portraits of Khalid alone in domestic and public settings emerging out of barriers and darkness with patches of interstitial light. Towards the end of the chapter, her pregnancy becomes apparent as her upper torso is wrapped in a scarf as she is standing in the ocean with her back to the waves. Later, her son appears, playing under a scarf or sitting on a blanket and her photographs capture the joyous moments of motherhood tempered with the exhausting, long, sometimes lonely, days filled with walks to the park and kiddie pools.

Chapter two is largely derived from Khalid’s series Being Between, where the dupatta is featured heavily. Using a timer, Khalid inserts herself underneath dupattas in a wide array of colors and weights, attaining various heights and forms against a multitude of locales in the U.S. and Pakistan such as a beach, tire yard, park, Pakistani street, abandoned gas station, and fields. Based on their color and positioning, the dupattas take on different effects. One of the more visually arresting works from this series, Facing south, Khalid, dressed in all black, walks in profile view in a forest through knee-high wildflowers with a poppy red dupatta soaring overhead, triumphantly flag-like. In Seconds before leaving, Khalid packs a diaper bag with her son on her hip, the white duppata a floating specter above both of their heads. Remarking on dupattas in her work, Khalid said, “It’s protecting me, but it’s also following me. It’s hovering. It’s impressions of a culture that I’m adapting to, which is American culture, but it's also the culture I’m forgetting.”

Lali Khalid, Home. In my heart, beating far away. As the axis tilts, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

The third and final chapter deals more with the issues of “otherness” that Khalid faces as a Pakistani citizen living in the United States and dealing with the bureaucratic nightmares of citizenship applications and the family court law system. In The sun will go down, Khalid sits in the middle of an institutional folding table clutching her passport. The angle is slightly tilted to the left to reveal a white man cropped just enough to see his professional attire, wristwatch, and Pakistani passport. In A number, not a name, Khalid sits in a courthouse bench wearing a green head scarf, her foreign status juxtaposed against a blurred-out portrait of a white man in the background. These angst-ridden scenes are peppered with the more banal scenes of domesticity such as urine-stained sheets and her son’s face made up with her stolen lipstick. The book ends with images of her son encircled in the light, suggesting that his experience in this country will be similar to hers. In one of the final images, his face sticks out from under her shirt (toddlers don’t understand personal space), the cloth acting as the umbilical cord described by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, connecting mother and son together for eternity. Khalid’s wry combination of real world “big” problems and the daily tribulations of dealing with a toddler deeply resonate with mothers and caregivers. The book ends with an image where she exhaustedly falls fully clothed on top of her made bed at the conclusion of a long day. A symbolic reaction of constantly being dragged into courts to retain, prove and establish her identity. WM